Qadira Locke

<コ:彡

Qadira Locke <コ:彡

ig @qadiralocke

twt @qadiralocke

Qadira Locke

(they/fae)

Palestinian-Lumbee artist and advocate.

Qadira Locke is a Palestinian-Lumbee artist focusing on Tatreez and Paper as mediums and using traditional Palestinian cross-stitch techniques and Indigenous quilt patterns as a means of cultural preservation through communal crafting. Seeing the labor-intensiveness of crafts as half of the art and its value in being shared.

“Your use of art when organized can make a really big difference on the campus that you’re working on, beyond just your individual art. ”

RL: So I’ll give a little like introduction of my thesis a little far in. I think the first half of this kind of like interview conversation is more of just like, getting to know you making sure that I’m not just spewing out information about my thesis without people looking at my book and being like, Who is this person interviewing in the first place? You know?

So, um, we’ll do that. And then the second half is more of just like, cuz I didn’t want these interviews to be very static. So the second half is just kind of little sillier questions, more unconventional questions. We’ll get to those.

But for now, can you please introduce yourself? Kind of like who you are, where you’re from, what your backstory with art and textiles, how you got into historic fashion and fabrics, yeah things like that.

QL: So I am Qadira Locke, Q-A-D-I-R-A Locke, for the record. But I go by they pronouns. And I am from South Florida, Fort Lauderdale. Whoo. But my family, on my mom’s side, on my mom’s side I’m Palestinian, and then on my dad’s side, I’m Lumbee, fucking from North Carolina? And so each of them have kind of have their own individual art styles and craft stuff.

So because I- let me just start from the fact that my dad would always take me to renaissance fairs when I was a child and I would see the parade and I would see all the big gowns and outfits and I was so obsessed with it because, you know, autism moment. And I’ve always known about tatreez, which is Palestinian cross-stitch embroidery beadwork. I had bought some beadwork, I’ve been gifted beadwork, my family is a very much a big jewelry family, you know, and stuff like that. And I had always seen like casinos around. But I never really engaged with it on a personal level, until I kind of realized through all my special interest research that I was having a very Eurocentric view on what it is I was interested in. And I was like, Wait, given cultural background, maybe this is not- maybe I shouldn’t be disinterested in the British monarchy, and like, artists and reformation or whatever.

And so I started kind of doing more to connect with my own style. I started being given gifts of tatreez. It was really interesting because as I started to express my interest, my family kind of realized that there was somebody that they could be like, Oh, thank God, someone’s into this.

RL: Yeah, don’t dilute the bloodline or whatever.

QL: Yeah, exactly. And so for this project, what I’m doing for my thesis is the material heritage of Palestine. So I’ve been going down, and I’ve been kind of taking things that I’ve been making through community effort of solidarity, things that I’ve personally been making, and things that I’ve been inheriting and trying to put them together and kind of a, like, the materiality of Palestine in small things in both crafts, but also just items that show where they came from, are so present, even when they’re not about Palestine for people that think about Palestine as often as they do.

And so it’s been really interesting because I’ve kind of been able to take all the things that I’ve been learning and kind of use this sense of like, I know a lot about textiles, my research to basically be able to get other people as excited as I am about how cool this little bitch ass glasses case is, but like, this is all hand stitched, you know.

RL: Oh, very detailed.

QL: So yeah, my thesis. And then sometimes I’ll just walk around and wear a cowboy outfit because I can, but it’ll always include some form of- you’ve seen the before? Yeah, you’ve seen this motherfucker.

RL: Yeah, I have. It’s very cute.

QL: And it’s like, people always comment on it. And I’m like, Yeah, you want to know what the real cowboy looks like? In a joking way, but in the real way of I think that textiles and culturally relevant explorations of motifs in your everyday life is so fucking important to the preservation of culture.

RL: Yeah, exactly!

QL: So that’s what I’ve been trying to do, that’s what I’ve been doing, that’s where my focus has been, hence the ceramic tiles. I’ve been trying to do my best to get other people to engage with creating art about culturally relevant topics, to use that as like, Hey, your use of art when organized can make a really big difference on the campus that you’re working on, beyond just your individual art.

Yeah, I just have a lot of stuff like Museum Studies, motherfucker. Oh, I was gonna tell you this because I don’t know if you know this. I’ll actually send you a photo of it right now. But my tatreez is in a museum right now.

RL: Wait, what? Oh, yeah, you semi-mentioned it, I think.

QL: I pulled like five all-nighters to get that because it was a 116-centimeter-long panel. And I had like two weeks to do it. And dude, this actually took so fucking long.

RL: I bet. I saw I think glimpse of it on your your Instagram, your little spam.

QL: My spam, yeah. I have the photo. But you have any questions? I don’t know if I answered your introduction question.

RL: Yeah, that was that was a good introduction. I was gonna say I like that you kind of include community within your thesis and your practice and like your mantra of, you know, we need to preserve this.

Because I’ve also been kind of doing that for my thesis, just like, I don’t like this gatekeep-y-ness that I- it’s not to call out the graphic designers that I personally know, it’s not like that. But I just do feel like graphic designers tend to have this gatekeep-y-ness like, design is for us only.

And like, what you guys do is arts, and what we do is so much better than that. Yeah, like, I don’t know. My whole thing is just kind of dismantling what it means to be an artist and designer. So I’m kind of inviting the community. You’ll see my projects later on when I post them, but yeah, I kind of want to hear more about this tatreez project and your thesis. Like, what have you been doing? What have you done? You know?

QL: Yeah, so, um, okay, I forgot it in my dorm. I really brought everything with me. I was like, everything I possibly would want to show you. But last semester, I hosted three different tatreez- for the record, T-A-T-R-E-E-Z T, tatreez. Basically, I held three seminars and I taught people how to do it, and we made a Community Living quilt. So basically, people each got their own- in the beginning, what they did was they got this thing called Aida cloth, and it’s basically what this cloth is. So you can see like the little holes in it? That’s what we use for cross stitch because it’s essentially a form of cross stitch where people refer to it as just embroidery. And that’s because you’ll either just do it on the Aida cloth or you’ll do it on the Aida cloth and another piece of cloth so that you can remove the Aida cloth and so it just lays flush against the cloth you wanted to embroider.

So I taught people how to do it to cloth and they got little squares, like this size, of just cotton quilt squares and then they did it and then I removed the cloth for them because that’s the most labor-intensive part of it. Oh actually have one that someone gave to me that I’d never removed it.

RL: Oh yes.

QL: So I basically taught them how to research and pattern archives and stuff. So this is one a student gave me

RL: *Gasp* Cute!

QL: These are two different people’s. So this one person that- this is a reoccurring motif that’s actually this, but it was a staff member so they wanted to try it. That is also two different pieces of fabric. And then this is my favorite out of the ones that people have done so that’s why I hadn’t added it to the quilt yet because I’m like, oh my god, it’s so cool. Oh, this is a Mother’s Day motif.

RL: Is it part of a larger motif?

QL: Yeah, and it usually has, like, an entire thing down below that has chickens, it’s really cute. But they decided to stop there. And I was like, that’s so fair, do what you gotta do? Yeah, I have a photo of the quilt, it’s in my room, I could send it to you.

RL: Sounds good.

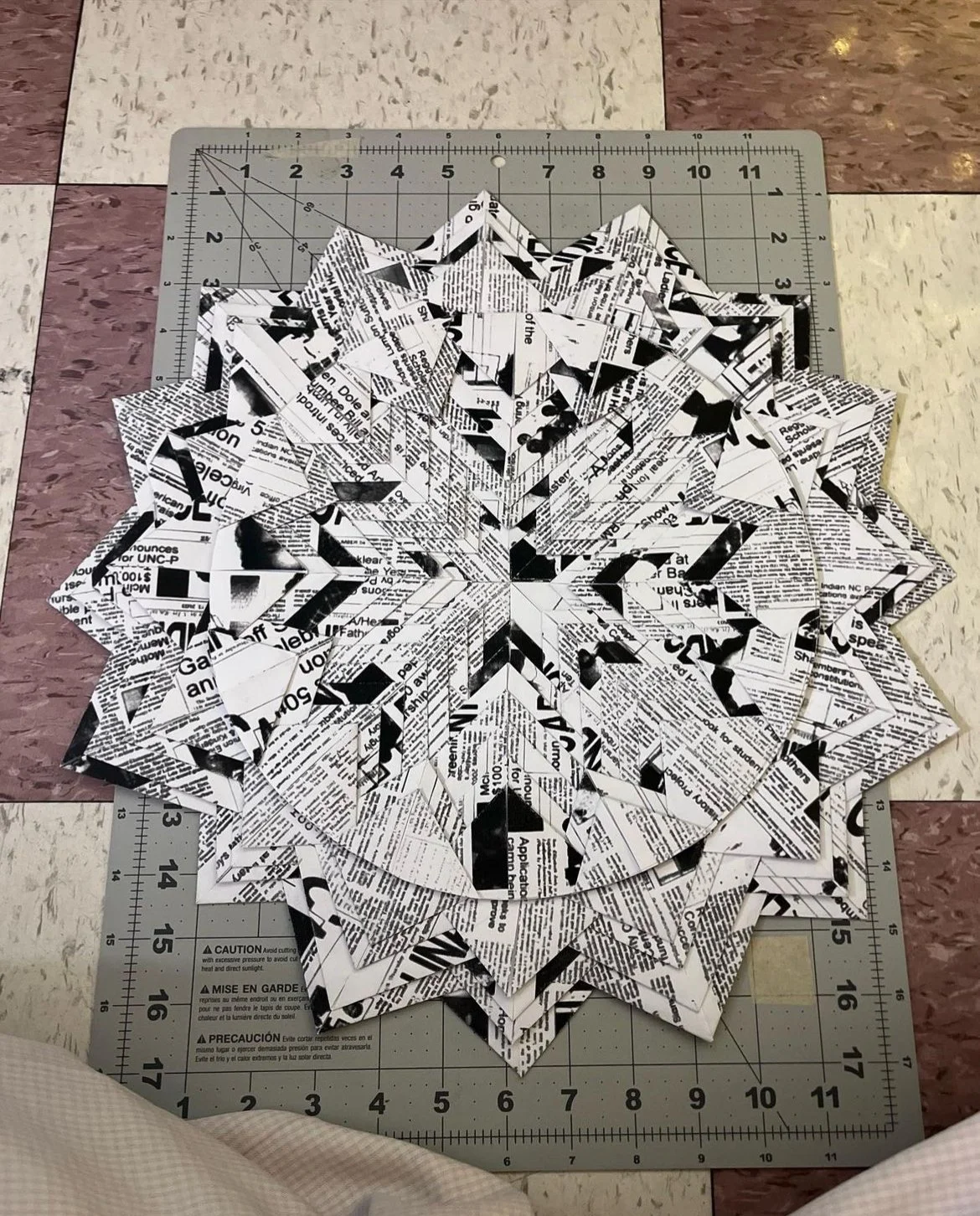

QL: But basically, I wanted this to be for my class on subjective archives. And so people kind of created art that was- the prompt was sitting with the materiality of something and sitting with materials and kind of reflecting on what you can do with materials. And I was like, I want to do it on tatreez. Because I had already done a project for the Lumbee side, for my last project, which was creating a large paper pine cone after the Lumbee built motif, using newspaper archives.

And so I wanted to do something with tatreez. But I also wanted a community engagement aspect of it. So that’s why I held those. And then this semester, because I’ve been doing a TA/co-teaching situation on the daily life in Palestine, which is a class that’s like an everyday ethnography where we go over different aspects of Palestine in the everyday format.

One of the things that I did was, I did a day where it was tatreez, and it was textile in full guard. And so I had everyone do tatreez while we were doing the class. And it was such a fucking, it was the most engaging class that we’ve had all semester, not to pat myself on the back too much.

But I also brought in extra ceramic tiles and I had them do those. And maybe this is just my own philosophy and education, but I found that students really, really engage with the material more if they have some sort of tangible activity in front of them. And I found that crafts, like textiles, especially textile art, even if they’re bad at it, I think it was really nice to see people engaging earnestly with it. And like, really, really, excited that they got like a tatreez done, you know, yeah. They were really, really fast at learning about it. And I was like, damn, good for you, you have amazing control.

But it was like never something that they would go out of their way to try because it’s like, you need materials, you need guidance, you know. And it was really interesting, because two of my students- here, I’ll show you. They’re amazing. Two of my students had already gotten into tatreez because they’re part of Students for Justice in Palestine. And I taught the tatreez like a while back and I’m supporting them in special projects after this, like during the second half of semester, where they’re doing these things called tatreez samplers, which- it’s basically like, you don’t want to get too committed to one big pattern so you just do a collage of smaller patterns. And I think they have examples of this from the 16th century of century samplers, like, these are old as fuck, but they’re so talented.

Like, I’m actually in awe and shocked. I’m gonna show you a photo because every time they come to me and they’ll show me their tatreez, and they’re always doing tatreez. And I’m like, Yes.

This is one of theirs. Oh my gosh. Oh, oh. And you see that right there? they actually gifted me one here. I’ll show you.

RL: That makes sense.

QL: Yeah. Um, but Tirazain and shout out to Tirazain because they have like a- they’re basically pixel art, did all of these fucking garments that have been electronically scanned into patterns so that they can remain online and open access.

RL: Let’s go, I love public resources.

QL: And there’s this concept I’m sure I’ve told you this, it’s my favorite thing to say because it’s kind of my ultimate like, mantra or whatever, Islamic flag makers would always make some sort of mistake in their work because it can’t be perfect because only God is perfect.

And so is this silly thing, like none of your artwork can technically be without fault. And I think that you see that a lot in tatreez and where it’ll be like unabashedly, there will be a pattern that has been halfway cut off, but it’s just like, it’s fine. It was in a row of like 16 of this pattern, you know, so no one’s paying attention to it in the grand scheme of the piece, but the artists definitely would know it’s there.

But it’s kind of one of those things that you just have to factor in when you’re making a piece you’re planning for this kind of design process.

It’s all part of the process if something gets cut off, or if something is distorted or something like, I can’t even explain to you how many times I had to adjust my entire pattern plan, because I forgot a row of stitches, where I accidentally added an entire row of stitches, and it was too late to go back.

Yeah, it’s called the feather motif and is supposed to have an entirely extra row. So the entire piece doesn’t have that extra row, because I just didn’t do it on the bottom row and I couldn’t feasibly fit it into the other ones.

RL: You just gotta ignore it and keep going.

QL: Yeah, you’re trying to make it as distractingly maximalist as possible, or all one color. So no one can really tell. That’s my, that’s my design process.

RL: I love that because embracing mistakes is what I love because I make a lot of mistakes in my designs as well. And sometimes I just get too lazy to fix it. And I just embrace, you know.

QL: It makes it more fun.

RL: Yeah, it feels more personal. Like a human actually made this.

QL: Nobody knows your piece like you know your piece.

RL: Exactly. So yeah, my thesis is just about shedding light on other types of design. And in the world of design, there’s just not only graphic design and we could learn a lot from other types of designers. There’s also a lot of shared common traits and stuff like that. And also, I just didn’t want to- I wanted to do a silly and fun thesis topic. I didn’t want to do a whole bunch of research on technology and how to change the world. I’m sorry, I do not have faith in humanity like that.

QL: Yeah, like it’s life or death depending on what font you choose.

RL: Yeah, like, oh, how does choosing this font save humanity? I’m like, this is not me. You know, I don’t designed to save lives, I designed to have fun. I can leave the saving lives to other designers if they want to do that. I just want to have fun with other designers and other artists. So that’s what these interviews are for. And also, I get to learn a lot about like other designs, like, um, I interviewed my friend the other day, who’s a glassblower don’t know anything about glassblowing. Like, I got to learn a lot about tatreez today. And, you know, the process of doing that. And also the way that like, it can be an art archive.

Yeah. But I have just a couple more questions, they’re a little more silly. They’re a little more like, you can go as hard into it as possible. You can answer it silly. You can answer it seriously. It’s up to you.

You like historic fashion, I know that. So, if you could time travel to any era solely fora its fashion, which era would you choose? And what would you wear? But also what would you study from that era because it’s like maybe the first ever people to create this trend or fabric?

QL: I have an immediate answer for this. It would be 1550-1560s Scandinavia because they had this fucking insane style of smokkr dress. Oh my God, and the sleeves are insane. I cannot explain to you how fucking weird it is and how much I’m obsessed with it because it was at a time when the decolletage and shit, everything was beading and pearls were the most sought after. Because it was when Queen Elizabeth the First was in rule. Yeah, yeah, I would want to see that shit in real life.

RL: I don’t know what they look like, but I’ll ask you for a picture later, or I’ll just search it up. Okay, next question. Have you ever experimented with unconventional materials in your textile designs, or not just you, but maybe someone that you’ve seen like one of your students? What was it? And how did it turn out?

QL: You know, something I’ve always been really interested in that I’ve really wanted to try is like screenprinting and then doing some form of traditional like cross stitch or embroidery over the screen printed to try to kind of change or enhance whatever it is you screen printed on.

I have not done it. And I’ve not seen anyone necessarily do it. I’ve seen people quilt screenprinted fabric and stuff, but that’s something that I really, really want to do. And I have my embroider machine and want to start doing it because I think that that would be a really interesting subversive, like, imagine big ass “X” over someone’s fucking face that’s been screened, like, how sick would that be?

RL: Fuck yeah. And would you ever think about like mixing tatreez with modern days of fabric making/styling?

QL: I actually have really thought about that, like starting some form of business because, you know, half the battle is in fact, doing the designing of tatreez patterns.

RL: Yeah, true.

QL: So part of me is like, it’s still technically tatreez, as long as it’s the style of the x’s on the fabric, you know because a lot of the $450 bulbs that I wear are fucking expensive to ship, but they’re all machine embroider. Because you can’t expect someone to hand embroider a foam that big now, and you have the technology. But they are able to mass produce so many different styles. So I’m like, I would think that really cool if I could combine like actual tatreez with like machine tatreez, and with other elements of like embroidery.: The blockchain is like- it’s not 1300s Remember? It might be 1400 Hold on.

RL: Could be a cool future project.

QL: I’m saying, like.

RL: And for the last two minutes, if you could collaborate with any historical figure, or someone who’s famous in the fashion design field, um, if you could collaborate with them, who would it be? And, what would you create together?

QL: So in high school, maybe I’ve said this before, I had to do a project- basically a case study on some sort of famous designer, and I decided to do it on Rei Kawakubo. I think she’s still alive. But she’s probably my favorite designer because of her, “Black is not a color, it’s a palette” show. She basically brought the ripped clothing to runways.

Maybe I’ve introduced this to you too. She brought the rips she brought black as into high fashion, in a sense that, um, she’s just so cool. And I think that the subversion of like, taking something that I’ve seen so linearly, and being able to expand it in- just making people be able to visually see one element that they always thought was just one and make it something that can be conceptualized, like fucking theme. Yeah, it’s such an event and talent that I just wish I had. And I just respect that so much.

RL: That’s cool. But that’s really all I have for now. I think we have less than one minute, it’s gonna cut me off. But, thank you so much for being here and for having this little chat with me!

“And so is this silly thing, like none of your artwork can technically be without fault.”